On September 9th, Mario Draghi, former President of the European Central Bank (ECB), published the much-anticipated Competitiveness Report that had been commissioned by the European Commission. As one might expect, the high investment needs and the proposal to use co-financing for part of the investment took up a significant portion of the media space in Finland. However, as the President of the ECB understands quite well, financing is the easy part. The hard part is understanding what concrete changes are needed in Europe in order to meet climate goals and other targets, and how to bring about those changes. Draghi has spent a lot of time thinking about these very issues and is clearly trying to elevate the level of debate concerning them in Europe. Two thirds of the more than 300 pages of Part B of the report outline sectoral snapshots and propose sectoral measures. I will highlight some important aspects of the report and examine them from the perspective sustainability sciences. It would be a pity if the public discussion of the Draghi report were reduced to the knee-jerk reaction “A collective debt? — No”.

“Mario Draghi, European Parliament, Plenary session – The future of European competitiveness, 17/09/2024”, Source: European Parliament

In his opening words, Mario Draghi paints a powerful picture of a dwindling Europe at a time when the world is rapidly decarbonising its economy and technological progress is advancing by leaps and bounds. In the 21st century, the US has led the way in the most complex technologies and artificial intelligence, while China has invested in the value chains required for the electrification of energy and transport, ranging from raw materials to the finished products. Despite good starting points, such as high-quality research, Europe has been left behind. The war on Europe’s borders and the disruption of the flow of fossil fuels from Russia suddenly put Europe under much greater strain. The automotive industry, for example, which is so important for Europe, is struggling because it has not been able to modernise in time. In keeping with current fashion, Draghi is making his argument through macro-level abstractions such as economic growth and productivity, but this is not necessary. They are not essential if we want to understand the evolution of economic structures and the relationships between different economies.

Climate change, competitiveness and geopolitics play the same game – and then there’s AI

Draghi takes climate change, competitiveness and geopolitics seriously and discusses their interplay throughout the report. Draghi is firmly committed to Europe’s climate targets, which are more stringent than those of other countries and continents. But achieving these targets depends on international competition and other external relations, because Europe cannot decarbonise even its own economy, let alone the global economy, on its own. Some technologies and solutions are cheaper to buy from China than to make in-house, but Europe will be in trouble if it cannot design and manufacture a sufficient share of what it needs. In any case, Europe will have to source many raw materials elsewhere. If Europe’s own production is not competitive and if Europe does not have enough to offer to others, these purchases will become unacceptably expensive. Too strong dependence on other countries exposes Europe to large price fluctuations in normal times and to exploitation and blackmail in times of crisis. It is an important strategic question which kind of production Europe can manage, now and in the future. It will not be resolved without careful planning in the Member States and especially at European level.

The treatment of AI is more blurred in the report. Draghi sees AI and complex digital technologies and services in general as important drivers of productivity growth. But what does it mean to say that Europe should integrate AI into all sectors of its economy? So what do we do in practice? I have no doubt that Europe should be at the forefront of AI development, at least in the sense of understanding it, researching it, and developing new potential solutions. But the rush towards adopting and deploying something that we don’t quite see the benefits of is still worth a critical look. When you compare the clarity of the arguments, the difference with basic industry is striking: in the foreseeable future we will certainly need steel, cement and various chemicals, but the fossil fuels now required to make them and the greenhouse gas emissions from their manufacture must be eliminated. That is certainly worth investing in.

Modernising basic production and stretching technological frontiers require different policy measures

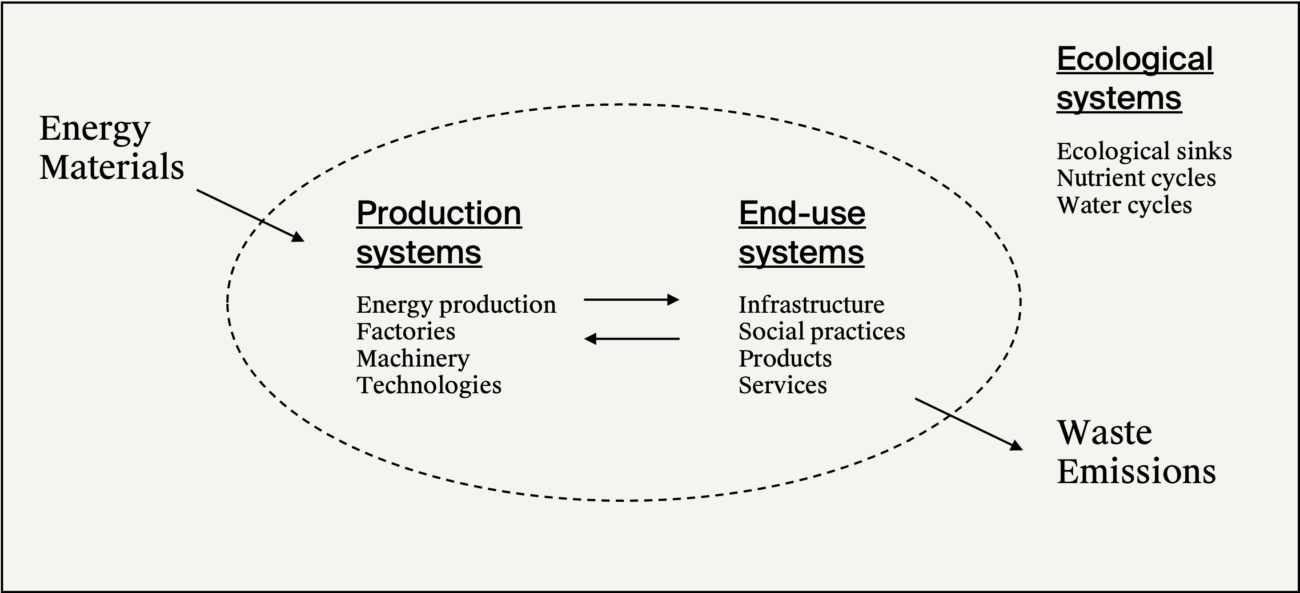

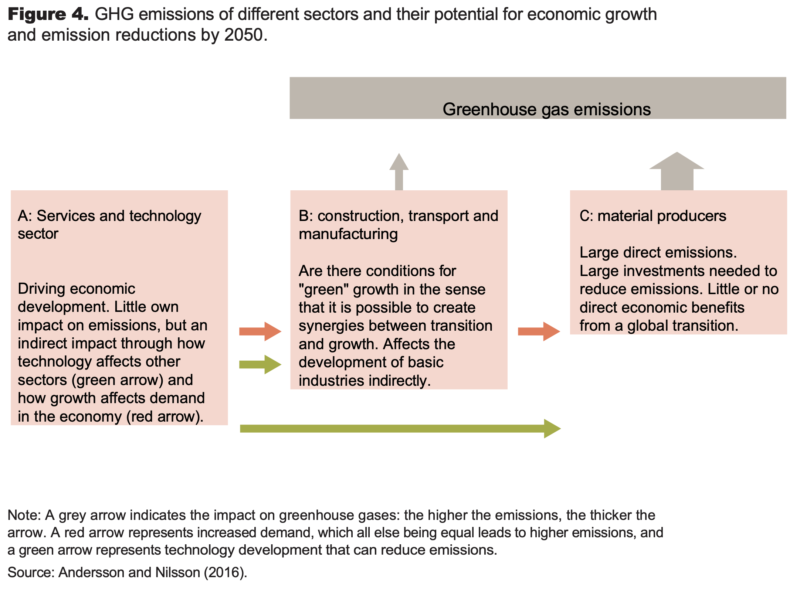

When I read the sectoral analyses, I see a background structure of industrial sustainability transition (see figure below, translated from Andersson, Bauer and Nilsson 2024). On the right-hand side of the structure is the production of basic materials, which is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions and requires large investments to decarbonise. There are no high expectations of increasing returns and productivity. In the middle are activities such as construction, transport and manufacturing. They do not generate as much direct emissions, but developments in them will affect the demand for basic materials. On the left are services and technological developments, which are the main focus of future economic expectations – the high yield -seeking investment world revolves around this (compare the development of the US in the 2000s relative to Europe as described in the Draghi report). Services and technological developments have little impact on emissions in their own right, but the impact on other sectors is considerable.

Figure: Classification of economic sectors and interactions in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and growth potential. Translated into English by DeepL from Andersson, F.N.G, Bauer, F. and Nilsson, L.J. (2024). Politikens roll för näringslivets klimatomställning, SNS Förlag.

Draghi is concerned that Europe has done rather badly on the left side of the structure in recent years, but he does not forget either the massive investments needed to upgrade the production of basic materials and to build, for example, energy, transport and defence systems in the coming years. Draghi recognises that achieving the objectives of these different sectors will require different policy measures (the proposed measures are partly horizontal, partly sectoral). Cutting-edge thinking and experimentation that pushes the technological boundaries cannot be guided by clear pre-set targets. Rather, support must be first given to diverse development, and only when promising starts are identified, more focused investment is viable. On the other hand, decarbonising energy-intensive industries and developing Europe’s energy, transport and defence systems require a strong emphasis on planning, collective choices and coordinated investment – and here the role of the public sector is absolutely essential (not forgetting, of course, the role of businesses and research institutions). I prefer to describe this with the term ‘infrastructure upgrade’ or ‘system upgrade’, although this is also a creative and innovative activity. And sometimes it also requires technological leaps. Take the electrification of a pulp mill, for example: you need to solve the problem of generating the necessary heat effect electrically and then processing the raw materials that are not burned into valuable battery materials, for example.

Is Finland listening? investments in upgrading energy-intensive industries often lack a “business case”

That different policy instruments are required to reform different sectors of the economy, is an important observation for Finland, which has the largest share of energy-intensive industry in the economy (in terms of value added) in the European Union, and an exceptionally large share of greenhouse gas emissions in the economy as a whole (about a quarter if the land use sector is excluded). Business and government also want to see more production facilities in Finland that benefit particularly from low-cost electricity, i.e. energy-intensive industry.

According to the Draghi report, the business case for investment in the renewal of energy-intensive industries is in many places poor or unclear (Part B, p. 99). In addition to the high direct capital costs, the operating costs are unclear when less well known technologies are introduced. Emissions trading and the future Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will help, but probably not enough. There is generally no significant additional market return available for green products compared to non-green products to cover the higher costs. In Finland (and Sweden), the situation is easier than in other European countries because the electricity required by the new technologies is available at relatively low cost. However, it is difficult to mobilise investment without significant public investment, even though it is recognised that emissions need to be brought down and industry needs to modernise to remain competitive in a remote corner of Europe. The required public investment is both financial and related to research, coordination and regulation (see also Löfgren and Rootzén 2021). In a recent research essay, Löfgren and colleagues (2024) outline how such state-level or EU-level industrial policy can preserve the useful features of technology neutrality while making clear choices about technology domains.

The European Union’s new economic rules, the so-called fiscal framework, look set to shrink Finland’s public investment capacity even further in the coming years – more than that of most other euro countries. Therefore, Draghi’s proposal that a significant part of public investment should be made through a Europe-wide shared financial instrument should be particularly attractive to Finnish policy makers and industry. A report authored by Raimo Luoma, published by the Confederation of Finnish Industries in February 2024, which sought to pave the way for the Finnish debate, tried to take the argument in this direction. However, according to public comments made when the Draghi report was published, Finland is still not ready for this.

The climate is really warming and natural resources are limited

Finally, a word from a slightly broader perspective. Namely, while the Draghi report takes global warming and the decarbonisation challenge seriously, it is still far from the reality where we will have to rapidly prepare for the increasingly dramatic effects of warming. We will have to cope with intensifying and more extreme weather events and invest an increasing share of our spending in climate disaster repair projects. We will also have to cope with the social unrest caused by these events. Deepening economic austerity measures and their essential element of ‘planned unplannedness’ (the political idea that we should not collectively think and decide at all about what we do, but only try to keep the market functioning properly) is probably not a very good starting point in such a world.

The picture of finite material resources created by the report is also confined rather tightly to the geopolitical perspective, where finiteness is conceived mainly as the ability to extract materials from the world for European use. In Draghi’s picture, the economy is not directly constrained by, for example, the limits to the sustainable use of natural resources and the maintenance of biodiversity. Including such factors would create considerable additional challenges for the rapporteur. If we go back to the classification proposed by Andersson, Bauer and Nilsson (2024), where the middle of the spectrum is, for example, construction and transport, both can be influenced enormously at the level of urban systems. If urban transport is largely public and buildings are repaired and modified rather than demolished and replaced by new ones, the climate and material burden will be at a completely different, i.e. lower, level. This will of course also have an impact on the factors of economic growth.

Draghi sometimes talks about the circular economy (for example, that because Europe has few virgin materials to mine for decarbonisation, increasing the recycling rate will give us comparative advantage), but this view misses the essential point that a high circular economy rate is impossible to achieve if absolute consumption levels keep rising.

Finally

All in all, Mario Draghi’s Competitiveness Report is very important reading across Europe. It is not (just) grey administrative rhetoric, but it also aims to reach a wider audience. One of the main merits of the report is its qualitative approach to the needs for economic change, rather than a ‘horizontal’ or ‘non-contextual’ approach. It also provides thoughtful advice on how to achieve these changes. In this paper I have highlighted only a few of the aspects covered in the report, and of the many sectors I have focused mainly on energy-intensive industry. As said, the Draghi report does not limit itself to these. I sincerely hope that the report will not just be read cynically from the perspective of the political campaigns of the day, but will be carefully studied and will form the basis of a broad social debate.

Paavo Järvensivu

Doctor of Business Administration, Associate Professor of Environmental and Social Policy