The Dasgupta Review (2021) was both lauded and criticised upon its publication. Criticisms tended to focus on economizing Nature, ”laying a price tag on Nature”. However, such criticisms miss the mark in two key respects. First, the notion of biodiversity in the report is surprisingly nuanced, and secondly, Dasgupta is adamant that determining the “price” of Nature is crucially a matter of politics. Critique of The Dasgupta Review needs to delve deeper, and this is important in the context of the ongoing Kunming Process and the calls for ”Paris for biodiversity”. The key problem is that although the report at times recognizes the functional importance of biodiversity, its role in maintaining and renewing the crucial flows of energy and matter underpinning all life, in key sections this understanding fades away. But biodiversity is a key concern in all areas of life, also in the environments where humans live and produce things, not just a question of protecting or conserving Nature as a separate realm.

Biodiversity, having for a long time been the stepchild of environmental awareness, has finally broken to the fore in recent years. The old gripe about climate change overshadowing biodiversity decline no longer seems that apt. The phrase “the sixth mass extinction” has become common currency – perhaps heralded by “the insect apocalypse”, which made us aware that not only are those buzzing bees threatened but also a host of stinging and swarming and crawling critters. Existential crisis hits all creatures great and small – and all things dull and ugly, as the Monty Python song goes.

The first full report by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) was published in 2019. IPBES has often been called “IPCC for Biodiversity”, and its reports draw their inspiration from the climate reports: gathering together all the latest scientific knowledge about biodiversity decline in order to foster stronger policy. The first IPBES–IPCC collaboration, the Workshop Report on Biodiversity and Climate Change, was published in June 2021, emphasising the connections between these crises.

Seeing as the accomplishments of decades of global climate policy are not that laudable, that may not be the most inspiring model, but still calls for “Paris for biodiversity” have grown, especially during the continuing pandemic. The previous attempt, the Aichi Targets (2011–2020) by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), was an abject failure: none of the targets were met. The latest incarnation was the Kunming Declaration in October 2021 – declaring that something should be seriously considered in May 2022.

The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review, commissioned by HM Treasury in 2019 and published in February 2021, arrived thus in a favourable climate. It was immediately compared with the 2006 Stern Review, an influential economic analysis of the costs of climate change. Launching a prestigious economic reading of the biodiversity crisis would hopefully lend the topic the kind of gravitas needed in the halls of economic power.

Alongside vocal praise, the review was immediately criticised for “economizing Nature”, “justifying the financialization of Nature” and “laying a price tag on Nature” et cetera. It was thus interpreted as an act of justifying the economic discipline against environmentalist critique and seen to be appropriating the whole issue into the territory of economics. Some of the rhetoric in the Review surely seems to serve such purposes:

Economics provides a remarkably effective language in which to read the socio-ecological world. The problem is not with economics, it is rather the fundamentally flawed reading of the structure of economic reasoning. (Dasgupta 2021, 130)

To detach Nature from economics is to imply that we consider ourselves to be external to Her [sic]. The fault is not in economics; it lies in the way we have chosen to practise it. (Dasgupta 2021, 310)

So the fault is in ourselves, dear Brutus, but who exactly is “us” here? Is it the legion of laypeople who have deeply misunderstood the nature of economics, or is this aimed at his colleagues in the discipline of economics? The Dasgupta Review offers ammunition for both – and in the end it is the reception, the interpretation and the use of the document that determines its effects. If and when it is seen as an act of justifying dominant economics (remember: “the fault lies not in economics”), it will no doubt also have such consequences. Interpretations more critical to dominant economic thought, practice and rhetoric, on the other hand, should have ramifications to that effect.

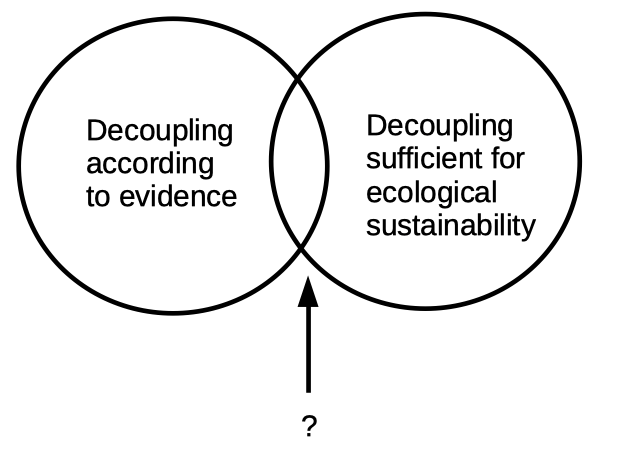

However, mostly absent from the discussion has been the question of how the Review handles the issue itself, biodiversity. This is crucially important, since the way biodiversity is understood determines what kind of “economizing” is even theoretically possible. It is my contention that the nuanced conception of biodiversity in the report actually detracts from the simplistic approach of “price-tagging” and commodifying Nature. Critique needs to delve deeper.

Not just about the headcount

For the wider public, and quite likely for the majority of decision-makers, economists and journalists, the most familiar manifestations of the biodiversity crisis are lists of endangered and extinct species. Accordingly, biodiversity is seen as an issue of less vs. more: the more species there are, the better. Nature is the Library of life, full of unique editions handed down by history, and preserving as many as we can is the metric of success. Some sections of the library are more packed with books or have a selection of the rarest titles; ergo, they are more valuable. These are named “biodiversity hotspots”, upon which our most forceful endeavours of protection should focus. Coral reefs, the lush rainforests and the like.

However, species richness and extinction rates is only one dimension of biodiversity, and it does not really work as a proxy metric for the whole issue. In this, biodiversity differs essentially from climate change. In a very real sense, climate change is one phenomenon. Although emissions stem from diverse sources, and their socio-economic backgrounds vary enormously, as do the effects suffered around the world, all emissions still take part in a unified global climate system. Greenhouse gases, annual emissions and current concentrations in the atmosphere afford a clear and properly justified metric of success and failure. As Dasgupta notes, climate change is not representative among a myriad of environmental problems (Dasgupta 2021, 27). Biodiversity decline does not have a similar systemic unity; it is rather constituted of a plethora of phenomena.

Nature is not a library whose contents can be tallied and categorised neatly, with readymade niches found on shelves – the books and the shelves transform over time. We still of course use the Linnean system, but adjusting it to fit an evolutionary worldview requires constant reshuffling. Nor do the myriad ecosystems of the planet form a unified system similar to the global climate system. Actually, if natural systems were unified in a tight manner, they would not have the kind of resilience that has allowed life to slowly recuperate from astonishing disasters throughout history. Therefore, one common metaphor for the biodiversity crisis is deeply problematic. Imagine you are sitting on an airplane, and the passengers are casually removing a screw here, a rivet there, and a bolt somewhere else. For a long time, the airplane keeps flying along just fine, until a critical boundary is passed, and the plane breaks down and crashes. But as L. B. Slobodkin has noted, there is no airplane: nature is not a single mechanism, so everything does not crash at once (Slobodkin 2001). Not with a bang but with a whimper goes the biodiversity crisis.

Nature is a mosaic, an assemblage of partly intertwined and partly separate ecosystems, working on different spatial and temporal scales. Of course, everything takes place on the same planet, but life’s ability to carve out habitable spaces practically everywhere, overlapping and intersecting, ecosystems within ecosystems or even within individual beings, makes the planet an absurdly vast place. Bigger on the inside, truly. Life creates space for itself – the habitable niches do not pre-exist; they are carved out by life’s processes. Barring a celestial disaster, everything cannot crash at once.

From this it follows that neither is biodiversity a unified phenomenon that can be properly measured by the number of species (those metaphorical bolts, screws and rivets). Like Dasgupta states, it is not a question of “a mere headcount of species” (Dasgupta 2021, 36). In addition to the diversity of species, there is the question of diversity within species: the genetic diversity of populations. And that is crucially “populations” in plural, since the fate of individual populations across the world is also of vital interest. A species may survive, but countless local populations can become effectively extinct, which can have huge ramifications in the world. This was pointed out by the renowned fisheries expert Daniel Pauly as he noted that the world does not lose abundant animals, only rare ones. That is, too much focus on the absolute extinction of species detracts attention from the background hum of biodiversity decline, as populations shrink and become genetically less diverse, and as species disappear from some areas of the world, changing the world fundamentally, a long time before the final lights of extinction wink out.

This points to another key dimension of biodiversity, their functionality. Just by looking at the headcount of species in a particular area, things may look fairly good for a long time, even as the state of ecosystems slowly degrades. The ecosystems may already have become dangerously compromised, irreparably even, before we notice a rise in local species extinctions.

This diversity of biodiversity is a widely recognised issue in science, even though awareness has not spread well enough to the wider public. One important scientific discussion considers functional diversity, the existence of functional traits in an ecosystem that maintain its central operations such as decomposition, circulation of water and nutrients, fluctuation of relative population sizes etc. The viewpoint of functional diversity is concerned less with the presence of particular species rather than the key functions taken care of in particular ecosystems – the precondition for their continuing viability and resilience in the face of disturbances and change. The old adage that the more species you have in an ecosystem the more resilient it is, appears to be questionable. It seems that the presence of key functional traits is the major factor.

It is however crucial to note that functional diversity cannot offer an alternative universal metric for biodiversity, as opposed to species headcounts. Function always appears in a context, a historically inherited situation of particular ecosystems. The importance of functional traits is realised in that conjuncture, and their value cannot be generalised globally. Thus attempts to make global functional trait inventories after the model of (species-focused) biodiversity “hotspot maps” would be very questionable. The diversity of biodiversity means that we will always need several parallel metrics and approaches to analysing and measuring biodiversity, and some of them need to be context-specific. There is no master metric.

The viewpoint of functional diversity reminds us that change is a natural feature of ecosystems, and not only seasonal or other circular change but also the transformative change of ecosystems over time. Resilience is not just recovering from shocks but also transforming and surviving in a new form in new circumstances. However, discussion of change in relation to biodiversity can be a touchy topic. On the one hand, evolutionary change and the constant fluctuation of ecosystems in the face of changing circumstances is what in the end makes biodiversity possible and ecology understandable. But on the other hand, there is a strong Western cultural tendency to consider one particular historical constellation of nature as the one to be preserved: the authentic, intact Nature. This is deemed more valuable than nature compromised (corrupted?) by human activity, with the attendant aversion towards discussion of change in nature – it is easily assumed to relativize the changes wrought by humans in this world. If all that is constant is change, why worry about human impact on the environment? This old quasi-conundrum seems to be an especially hardy weed in the case of biodiversity.

But change is necessary. It is neither good nor bad: its effects are determined by the pace and frequency of changes in circumstances, the abilities of adaptation and migration, the time it takes new ecosystems to get established, whether there are concurrent disturbances and so on. This was true even in the absence of humans. There have been several mass extinction events in deep history, after all. The inevitability of change is a crucial feature both for understanding biodiversity decline and for our attempts to protect biodiversity.

The problematic attitudes to change were exemplified by a 2019 study published in Science that revealed a pattern of local species richness gains and declines globally, instead of a general decline (Blowes et al. 2019). As the researchers pointed out repeatedly in interviews, at this stage the picture of the biodiversity crisis is more that of large-scale reorganisation rather than of primarily species losses (Kaplan 2019). That is, the global view of species decline is not reflected one to one on the local level. The key question of course is whether these local stories are about adaptation or homogenization etc. Compositional shifts can herald future changes of many kinds, and some of them clearly can involve accelerating extinctions and spread of “generalist” species. Still, the publication of the study sparked a concerned debate whether the study underestimated the urgency of the biodiversity crisis – the background assumption clearly being that species extinctions are its most important form, and that detracting from that focus can be dangerous. The cultural tension between notions of intact nature vs. change is visible even in scientific circles.

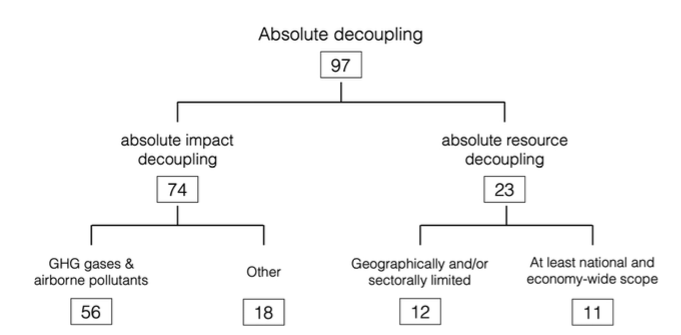

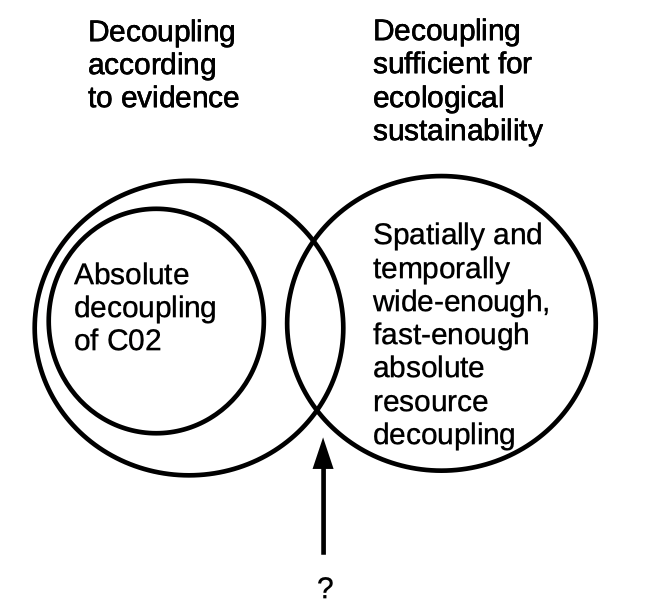

The drive for a master metric

The diversity of biodiversity and the pros and cons of various metrics are ongoing topics of debate in science, but in general scientists favour a plural approach to this complex issue, as Dasgupta rightly notes. However, in the world of policy, there are strong pressures for finding straightforward environmental metrics. Climate change tends to be the representative model: we need one master metric like the carbon dioxide equivalence of various greenhouse gases to set common goals in order to forge “Paris for biodiversity”. As one key political figure in the Finnish center-right stated, we need clear numbers about species to be protected in order to craft a viable policy. Basically: how much biodiversity do we need and want? Less versus more. However, as we have seen, the mosaic of biodiversity decline does not lend itself to such a simplistic approach. The problems are at the same time local, regional and global, and the socio-political dynamics behind different forms of biodiversity decline, and their effects, vary enormously.

Blair Fix has shown how this “aggregation problem” arises repeatedly in environmental issues (Fix 2019). In trying to aggregate incommensurable things, it is necessary to choose a single unit of analysis, and this will always depend on one’s goals and the underlying theories. Biodiversity, as we have seen, is a host of incommensurable phenomena that cannot be meaningfully reduced to one metric, say, the number of species or the aggregate area of protected nature. In such cases of substantive incommensurability, aggregation inevitably gives rise to serious practical biases and should be avoided.

Choosing species number as the dominant dimension of biodiversity tends to favour decisions that maximise that number, irrespective of population vitality, of the fate of local populations, and of the state of ecosystems in general. Thus, for example, vulnerable local populations of widespread and globally abundant species seem less important, even if they may be functionally vital in the local contexts. This is of course not to say that the full-scale extinction of endemic species (living in only one geographical area) is not truly a tragedy. Losing rare species at an accelerating rate takes away something from the world. Keeping some areas devoid of intensive human activity is important. But this shows how the choices involved in aggregation affect policy and can leave some dimensions of biodiversity decline in the shadows.

Prioritising biodiversity policy on the basis of global “hotspots” is another good example. Again, there are very good reasons to try our best to protect the remaining rainforests, wetlands and coral reefs, and many other threatened biomes. But deciding aggregate global priorities on the basis of such mapping means that many other areas are deemed less important or even meaningless, biodiversity-wise. Negative environmental impacts that take place in many wealthy countries are deemed less important than those that happen, say, in the tropics, because tropical systems tend in general to be species-rich – but are “species-poor” ecosystems thus inherently less valuable? Recently there have been vocal scientific arguments against the primacy of global biodiversity protection priority mapping (Wyborn & Evans 2021). Global aggregation loses vital local information, but most conservation decisions occur at local level. So perhaps aiming for global biodiversity targets is not the best approach, at least when targets are set from a globally aggregated viewpoint.

In this way, the idea of biodiversity as a less vs. more issue gets very real. If the more voluminous and valuable biodiversity is seen to exist somewhere else, it is tempting to say that it is not that useful for us to focus on actions over here. Such rhetoric has been a familiar feature in climate debates of wealthy countries, but the freeriding logic is even more tempting vis a vis biodiversity, since scientifically problematic aggregation actually can end up supporting it. You can follow the science and go wrong. In Finland, such rhetoric has increasingly been used to question the necessity of nature conservation, especially vis a vis forestry.

Such an approach tends to focus on labelling and certification schemes and boycotts of especially bad products. This means that less attention is paid to the background hum of biodiversity change: increasing extraction of natural resources, land-use change, intensive use of agricultural chemicals and other threats like climate change. These are the big drivers of biodiversity decline in its multiple forms. This is a crucial issue in the era of multiple concurrent environmental problems: even in the best of possible worlds, many things will be inevitably lost, and all will have to change and adapt to the new more uncertain times. Ensuring the capabilities of adaptation and transformative resilience, and taking care of the operation of crucial cycles of energy and matter in the environment, must be key viewpoints of biodiversity policies.

So, biodiversity as a mosaic phenomenon does not aggregate in a fruitful way, but environmental policy especially at a global level tends to require aggregate metrics. This is a truly wicked problem for biodiversity policy. Species numbers and the extent of protected areas tend to be the fallback positions, even though the scientific problems relating to that exclusive focus are well known. The Kunming Declaration includes a call for the protection of 30% of land and sea areas. But as this indicator transitions to de facto policy, it gives rise to a host of potentially perverse outcomes (Barnes et al 2018). Would the choice of protected areas be determined by sensible criteria? If for example success is measured primarily by the number of species, would those protected populations be viable in the long run against the great churn of our age of acceleration? A whole other can of worms is whether the 30% rule would amount to an unprecedented land grab from indigenous communities and other vulnerable groups.

And most of all: what would happen in the 70% of the world? This is not a trite notion: self-styled ecomodernists or accelerationists are constantly pushing the idea that human activity should be intensified to the extreme in the areas of human production and habitation, leaving potentially more and more areas for “intact” nature or for areas to be “rewilded”. The potential merits of rewilding aside, the idea is basically that wrecking the rest of the environment is fine, as long as we humans leave an increasing portion of the planet for the rest of nature. Of course, since over 40% of the ice-free land surface of the planet is taken over by agriculture, and 80% of that represents animal production, there surely would be significant leeway , e.g., for reforestation, provided that the food system and consumption habits could change in tandem. Otherwise, we are back with the old problem of land grabbing and destruction of commons by enclosures. There are no socio-economic dynamics currently in place that could even begin to guarantee that “land sparing” would result in that land ending up as rewilded areas (Rasmussen et al. 2018).

Fortunately, not all calls for the 30% rule are based on such an extremist form of separation between culture and nature. One hopes that most proponents consider it important also what happens outside protected areas. Life matters everywhere. What’s more, “intact nature” simply will not remain safe and separate in its reservations. If our age of environmental crisis has taught us anything, it is that environmental problems do not remain limited geographically. Thus, what happens in the 70% would inevitably determine what happens in the 30%. If the metabolism of societies remains on its current trajectory of increasing use of natural resources, the results will be grim all over the place.

Dasgupta notes repeatedly that humans are embedded in the rest of nature, and this is inescapably true. The modern illusion of emerging independence from nature was only possible by increasing use of energy (mainly fossil fuels) and extraction of an ever more diverse array of natural resources. In fact, the material and energetic ties to the rest of the world became ever more convoluted: complexifying dependence instead of independence. Now the illusion is broken, and we should not resort to new forms of it, however ecologically sensitive they might look at first glance.

Flows, not only stocks

The Dasgupta Review fares surprisingly well in this regard, considering that too often economist readings of environmental issues are fairly simplistic and fall back on adopting climate change as the representative model of all environmental problems. Human embeddedness in the rest of nature is no empty rhetoric or smokescreen: the idea really runs through the text on many levels. In the picture painted by the Dasgupta Review, it really does not make sense to distinguish “environmental issues” as a sector of society that can be safely enclosed while the rest of society keeps chugging along – just as long as we set the prices right. Anyone who reads this message out of the review – either critically or as a source of self-justification – has not read it properly.

The diverse dimensions of biodiversity described above all appear in the text, and Dasgupta offers a nice set of pedagogical tools for laypeople (which in this case includes the economists) to understand why biodiversity decline is such a wicked problem. Nature is mobile, silent and invisible. Mobility means that ecosystems and the fluxes that keep ecosystems viable move over human-made borders – or if those borders have strong enough physical manifestations, said fluxes can break down. Silence means not only that non-human beings are unable to stand up to themselves, but most of all that natural systems do not give clear and unambiguous signals about when they are about to be seriously disrupted. Invisibility refers to the fact that countless processes take place on a microscopic level, and keeping tabs on them properly is virtually impossible.

In addition to this triad of features, Dasgupta emphasizes non-linearity, complementarity and non-substitutability. First, complex natural systems function in a way that surprising regime shifts to qualitatively new states can take place. Second, nature cannot be neatly separated into distinct parts or sub-systems, as intertwined systems are dependent on each other in many ways. Third, there are myriad features of nature that can never be substituted by others or by technological surrogates.

Another set of tools heavily used by Dasgupta is a contested one, and one that often invokes fierce criticism. Dasgupta talks a lot about ecosystem services. For many, the mere word “service” seems suspect, and they see it as fatefully linked to commodifying attitudes towards nature. Ecosystem service is seen to be an inescapably instrumental and anthropocentric notion and thus suspect. But since human life will always be dependent on the rest of nature, in multifarious ways, in any conceivable future, we will also need tools to understand that dependence in a more detailed and operationable way than just saying “we depend on Nature”.

In 2017, IPBES proposed another word to get around this terminological resistance: “nature’s contributions to people”. It is supposed to be a higher level concept than ecosystem services, one taking in diverse worldviews and especially indigenous knowledge. However, in practice the differences between the words seem to be very small (Kadykalo et al 2019). But fair enough, sometimes we humans need new words as bridges to new discussion, even if the different words really refer to the same things. (Other times, we need to fight over the meaning of old words.) However, if and when there is a tendency to “commodify nature”, it is questionable whether any new term will by itself get rid of that inclination. Any word like this will become an object of a struggle over definitions. Dictionary definitions will not solve the issue.

I think the main problem lies elsewhere. Both “ecosystem services” and “nature’s contributions to people” encompass so much that they end up referring to everything in our relationships to the rest of nature. Dasgupta makes the familiar distinction to provision services, maintenance services, regulation and cultural services. Sometimes people also want to include negative contributions or “disservices”, which really inflates the area of reference. If the reference of a term is too vague, it really stops working well as a practicable concept.

The trouble here is especially that there is no generic nature or biodiversity that offers these various services (leaving “disservices” aside). Different environments are more fruitful in one regard, less in others. A forest can be an environment for production of lumber, a sink and storage of carbon dioxide, a habitation for various species, a good place to forage berries and mushrooms, and it can play a part in alleviating the effects of storms or in rainfall and drainage patterns. But in forestry, some of these tend to be emphasised over others – usually the production of lumber – and this hurts other “services”. The biodiversity of forests develops accordingly in different directions in these diverse practical relations, depending on which “services” are emphasized. Some trade-offs are inescapable.

Since in any kind of sustainable future, humans will still need food and other things that depend on the living world around us, we cannot focus only on the kind of services and contributions that are dependent on more “intact” or “wild” nature, and on that kind of biodiversity. We need also to pay heed to the kind of biodiversity that is important in the environments where we produce things and where we live: the life in agricultural soil is a topical example, as is the fate of insect populations. Knowledge about the connections between allergies and biodiversity in one’s living environment is increasing, and of course, the links between biodiversity and zoonoses is a pertinent issue.

This is why biodiversity is important everywhere. And this gets more and more important every day: the historical era in which humans have tried to replace nature’s contributions with more and more intensive use of energy and resources is over, and we will have to rely on the environmental common goods provided by ecosystems much more (e.g. nutrient retention and cycling instead of intensive fertilization). This means in practice that the requirements of biodiversity in our production and habitation environments will change. But we cannot understand this by stating generically that we depend on “nature” or “biodiversity”: qualities are paramount.

The Dasgupta Review is somewhat uneven in this regard. Sometimes it is heedful of this complexity, at other times it reverts back to simplistic notions of biodiversity:

The distribution of the world’s natural assets – and their associated biodiversity – is uneven across the Earth. For example, 17.3% of the Earth’s land surface maintains 77% of all endemic plant species, 43% of vertebrates and 80% of all threatened amphibians, in 35 biodiversity hotspots. (Dasgupta 2021, 372)

But conceptualising nature as an asset in this way precisely makes it harder to understand the diversity of biodiversity: it is not a simple less vs. more question as this quote suggests – and the review denies elsewhere! Natural “assets” should not be quantified in such a simplistic manner, as it detracts from the key contextual understanding that the review’s otherwise more nuanced perspective on biodiversity fosters.

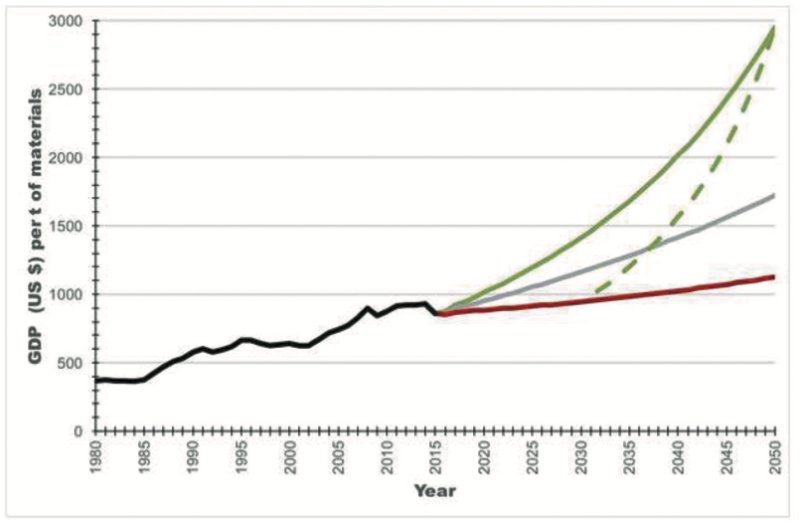

Dasgupta’s insistence on nature as assets does have some fruitful uses. He employs the notion to criticise the use of GDP to judge economic performance. As it is a metric of annual flows, it does not measure wealth or stocks of assets, especially depreciating them. Thus you can increase your GDP flow by burning through your assets as if there was no tomorrow. And societies have of course in many ways been doing just that. This is not only an environmental question: according to Dasgupta, GDP is not a good metric of any kind of sustainability. (Dasgupta 2021, 334, 343) It is a tool for very limited uses. He also importantly reminds his fellow economists, and us all, that you cannot measure the worth of nature by its productive flows alone. Nature does not maximize its net primary production, so for example net primary production (NPP) does not work as a master metric for judging the state of ecosystems either. As Dasgupta notes, biodiversity is not about enhancing productivity in this simplistic sense. (Dasgupta 2021, 60)

However, viewing nature as assets leads us to focus on stocks, and with the tendency of looking at biodiversity as a less vs. more issue, this means that the Dasgupta Review easily slips back into the simplistic reading of biodiversity. But as we understand both the diversity of biodiversity and the multifarious forms of ecosystem services or nature’s contributions to people, we see how biodiversity policy should be both about stocks and flows. It is not only about maximising the amount of species, or about maximising the extent of “intact” or “rewilded” areas. It has to be also about taking care of the vital functions and flows of ecosystems everywhere: the constant reproduction and maintenance of all natural systems. Our production environments are no less important here, especially as failure there can easily lead to more appropriation of new areas following land or forest degradation or, say, collapse of fish stocks. The notion of nature as assets runs into the deep problems of aggregation and incommensurability.

Politics is inescapable

Despite these problems, it is clear that the Dasgupta Review is not an exercise in price-tagging nature. Nature cannot be parcelled out in portions that could be independently valued and substituted. Some changes wrought by humans in the environment are so grave or unpredictable that they simply should be prohibited, as Dasgupta unambiguously states (Dasgupta 2021, 124). They are effectively priceless.

These statements in can easily be shrouded by the fact that Dasgupta still relies on the customary economic terminology of environmental problems as “externalities” and the question of “internalising” them. However, this is where Dasgupta most clearly engages in a struggle of redefinition and criticises the dominant way these concepts are understood and utilized. But the review may be a tad too clever for its own good, as the critical message requires some excavation and is thus easily lost in popular readings.

Dasgupta’s accounting prices and inclusive wealth, the proper prices and the calculations of wealth that take into account the importance of biodiversity, are key concepts in the review but also somewhat confusing ones. First of all, Dasgupta clearly does not mean them as actual, read-it-in-the-label market prices that would be somehow calculated, “internalising” environmental impacts and the importance of ecosystem services in this way. Such calculations would be hopelessly complex, and what’s more, they would encounter deep problems with incommensurability. Dasgupta talks about accounting prices as being implicit, with “indirect means” required to realize them (Dasgupta 2021, 496). By this he refers to taxes, subsidies, regulations, standards, offsetting and downright prohibitions. Such institutional actions affect the decisions and priorities of all economics actors and make accounting prices into a practical reality. For Dasgupta, the biodiversity crisis is not only a market failure, but also a policy failure and an institutional failure. Thus internalisation of externalities and determination of accounting prices does not only happen on the marketplace but in politics:

In democratic societies, differences in people’s assessments of accounting prices influence the policies requiring their use are selected. We may think of candidates for political office as bearers or carriers of contingent policies. It is then no exaggeration to say that citizens express their differences over accounting prices by casting votes on their favoured political candidates. This caveat should be borne in mind when mention is made of ‘estimating’ accounting prices. (Dasgupta 2021, 302)

Actually, Dasgupta states explicitly that political and institutional change is primary. The “fundamental failures” of those areas need to be solved, as “pricing and allocation of financial flows alone will not be sufficient to enable a sustainable engagement with Nature.” (Dasgupta 2021, 467)

Fateful effects of a problematic metric

Finally, I want to point out one serious problem in the review. Dasgupta introduces a familiar graph about the relationship of ecological footprint and income per capita (Dasgupta 2021, 120). One message of course is that the footprint of the globally wealthy or middle-class people is very large. Also while discussing global trade, Dasgupta notes that it has actually increased global inequality and led to a net flow of wealth to the centres of power and affluence. In this context this is a downright radical message (Dasgupta 2021, Chapter 15). The problem of global inequality and injustice is emphasised at many points throughout the text.

However, in analysing this graph, Dasgupta ends up with a problematic conclusion. Since the curve of the graph is convex, it “suggests, ominously, that egalitarian redistributions of incomes lead to larger global ecological footprints” (Dasgupta 2021, 120). Being a proper economist, Dasgupta adds “other things [being] the same”. So in a nutshell, if the poorer people of the world get at all wealthier, they will climb rapidly higher in the convex curve. Ecological crisis gets worse if we alleviate poverty. This grim reading resonates through the review in many ways.

But there is a serious problem: ecological footprint by the Global Footprint Network is not a proper master metric for the diversity of environmental impacts, unlike Dasgupta seems to assume. When scrutinised closely, the ecological footprint really measures properly only climate change emissions, and even those via a cumbersome proxy (Giampietro & Saltelli 2014; see more in Finnish). And if we look at the curve only from the climate viewpoint, the interpretation has to go into concrete details. The convex curve is so steep only if poverty is alleviated mainly by using fossil fuels; if not, the curve will be less steep. Everything changes, and the conclusion does not hold. Poverty does not need to be alleviated by spouting carbon dioxide – but poorer countries will of course need huge amounts of financial support to make the energy transition by overstepping the fossil phase.

But the Dasgupta Review is not about climate change, and Dasgupta notes elsewhere that we should not take it as a representative model. There are many kinds of environmental problems that do not aggregate fruitfully: thus there is not one unified curve of environmental footprints. Biodiversity decline takes many different forms, and it stems from diverse socio-economic backgrounds. Some forms are more connected to poverty and social fragility, others more to wealth and overconsumption. So alleviating poverty will also reduce some forms of environmental impact as it risks increasing others. There are both convex and concave curves. Resorting to a supposed environmental master metric sadly muddles the message of the Dasgupta Review, losing sight of the importance of equality and justice during the ecological transformation of societies.

Ville Lähde

References

Barnes, M. D. et al, Prevent Perverse Outcomes from Global Protected Area Policy. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2, 2018.

Blowes, Shane A. et al. The Geography of Biodiversity Change in Marine and Terrestrial Assemblages. Science 366/6463, 2019.

Dasgupta, Partha, The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review. HM Treasury, 2021

Fix, Blair, The Aggregation Problem, BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality, 4/1, 2019.

Giampietro, Mario & Andrea Saltelli, Footprints to Nowhere. Ecological Indicators 26, 2014.

Kadykalo, Andrew N. et al., Disentangling ”ecosystem services” and ”nature’s contributions to people”. Ecosystems and People 15/1, 2019.

Kaplan, Sarah, The world’s ecosystems are being fundamentally transformed in the human era. Washingon Post, 17th October 2019.

Rasmussen, L.V. et al., Social-ecological outcomes of agricultural intensification. Nature Sustainability 1, 2018.

Slobodkin, L.B., The good, the bad and the reified. Evolutionary Ecology Research, 3, 2001.

Wyborn C. & M. C. Evans, Conservation needs to break free from global priority mapping. Nature Ecology & Evolution 5, 2021.