Decoupling “environmental bads” from “economic goods” is continuously proposed as a crucial tool that economies should use in the face of critical environmental problems. Two articles recently published by BIOS researchers point to one of the problems with the proposal: so far, the decoupling that has been observed is not wide, deep or fast enough. This can be seen better once the magnitude and timescale of the decoupling needed for ecological sustainability has been ball-parked. We discuss the findings of the articles, and request everyone interested in the topic to contribute to an “open source” list of research articles that we have started.

Background

During the summer, two connected articles by BIOS researchers on decoupling, “Raising the bar: on the type, size and timeline of a ‘successful’ decoupling” and “Decoupling for ecological sustainability: A categorisation and review of research literature” were published in the journals Environmental Politics and Environmental Science and Policy, respectively. Their results were already discussed in a couple of articles by Nafeez Ahmed, in “Green economic growth is an article of ‘faith’ devoid of scientific evidence” and “’Green Economic Growth’ Is a Myth”. Here, we wish to continue that discussion and explain the thinking behind the articles. It seems to us that the discussion on decoupling would benefit from a more systematic attention to research results. That is why we are also starting to curate an annotated “open source” list of research articles on decoupling – and invite everyone to contribute and use it as they see fit.

But first, let us start from the beginning: why is decoupling receiving so much attention?

The motivation for the concept of decoupling

The main motivation for the attention to the concept of decoupling is easy to identify. Mainstream economic policies see economic growth a necessity for continued well-being, poverty reduction, upholding public funds and even for environmental improvements. At the same time, the current environmental impact and resource use of many national economies and their global sum is unsustainable. Consequently, if economy is to grow or even stay at the current level, it has to be decoupled from its environmental impact and fitted inside planetary boundaries of resource use.

Another important motivation is that decoupling would make possible market-based solutions to environmental unsustainability. Depending on the view on the markets, some political intervention in the form of legislation or taxation may be seen as a complement but at the extreme decoupling can be used as an argument against state intervention.

The problem we set out to investigate

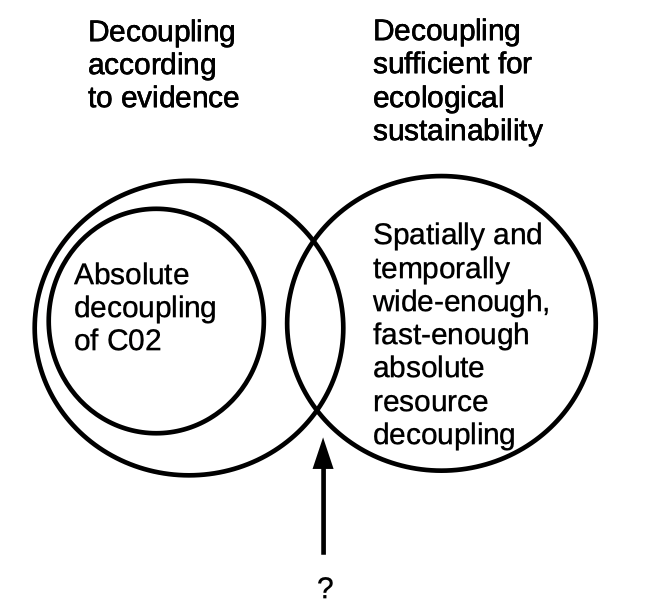

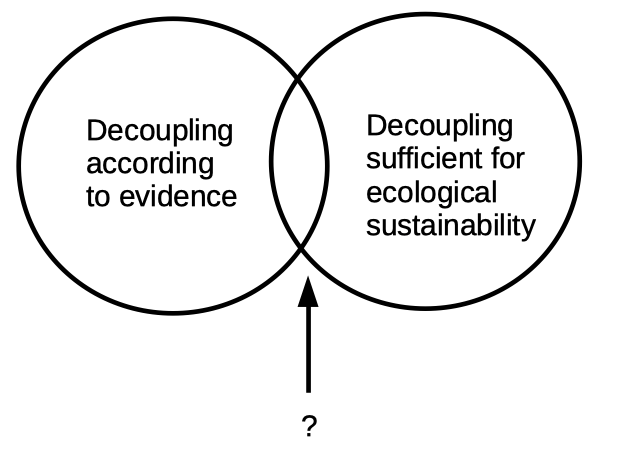

The problem with the proposal that decoupling is a crucial tool for ecological sustainability is simple. Decoupling exists. There is robust empirical evidence. However, the kind of decoupling that is empirically happening is different (even if necessary) from the kind on decoupling that is absolutely needed (sufficient) for ecological sustainability. The two articles discussed below were designed to address this question: what would successful decoupling look like, and what does the evidence in the literature say about its existence? How much overlap is there between “decoupling according to evidence” and “decoupling sufficient (and therefore absolutely needed) for sustainability”? What does the overlap consist of?

Is there overlap between observed decoupling and the kind of decoupling that would be sufficient for ecological sustainability?

On the types of decoupling

The question is made pressing by the fact that real world phenomena that are classified under the concept of decoupling are so varied that there is no necessary (logical, material) relationship between them. Quite the contrary: observed decoupling may be caused by recoupling elsewhere.

Types of decoupling may be categorised along different axes.

First, there is the spatial axis. Decoupling is discussed on various geographical scales, from the regional and national up to the global level. Obviously, decoupling on a limited geographical scale, such as a local region, is easier than on a wider geographical scale, such as a nation. For instance, a local region can diminish its use of chemical fertilisers, if it can buy foodstuffs with enough nutrients from outside the region, thus decoupling fertiliser use from GDP. However, when the wider context is taken into account, such decoupling disappears.

The second axis is temporal. Often, periods of decoupling are followed by periods of no decoupling or even recoupling. Making decoupling a continuous phenomenon is harder than achieving decoupling for a limited period of time, as continuous decoupling entails permanent changes in structures of production. For example, periods of decoupling have in certain areas of the world coincided with periods of economic downturns, and ended when economic growth has again picked up more speed.

The third axis is economical. Decoupling can be studied within one economic sector, or spanning many sectors, or across the whole economy. One of the problems widely discussed with relation to sectoral decoupling is the phenomenon of rebound or the so-called Jevons’ paradox. For instance, when energy efficiency is increased in a given sector, the result is sometimes increased energy use in other sectors. This means that evidence of decoupling in a given sector of the economy has to be analysed against the background of what is happening in other sectors.

It is also good to note that achieving impact decoupling is easier than achieving resource decoupling. Resource decoupling is typically discussed in terms of indicators like Domestic Material Consumption (DMC) Material Footprint (MF) and so on. These indicators combine information on a wide range of material resources, capturing a large portion of the “metabolism” of an economy. In contrast, studies of impact decoupling typically report the decoupling between one environmental indicator, such as CO2 emissions, and the economy. As noted above, such specific impact decoupling may depend on increased material and/or energy use. For instance, an economy may replace a harmful substance, such as ozone-depleting CFC gases, and thus be absolutely decoupled from the specific impact, but such a decoupling may be achieved by increased material use, if the use of the replacement demand more resources, such as energy.

Despite the inevitably rough generalizations of material flow accounts, they are the best available ‘proxy metric’ for the wide diversity of environmental impacts, including e.g. destruction of biodiversity, soil degradation or diminishing fresh water availability. As an International Resource Panel report (p. 47) puts it: “Environmental impacts – including pollution and climate pressure – cannot be mitigated effectively without reducing raw material inputs into production and consumption, because their throughput determines the magnitude of final waste and emissions released to the environment.”

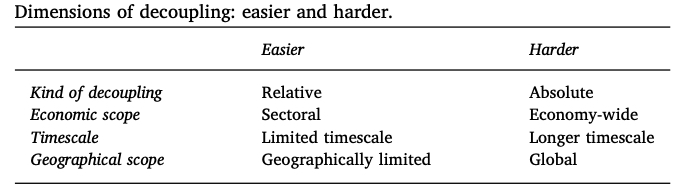

In sum, sectoral, temporally and geographically limited decoupling is easier to achieve than economy-wide, continuous and global decoupling. Obviously, relative decoupling, where environmental impact or resource use grows slower than the economy, is easier to achieve than absolute decoupling, where the impact or use declines in absolute terms. As presented in the table from the article “Decoupling for ecological sustainability”:

More importantly, sectoral, temporally limited and geographically limited cases of decoupling can exist in the presence of or even depend on no decoupling or even recoupling outside the analysed sector, time or geographical area. This can happen, for example, through creating and maintaining an international division of production where a developed country is decoupling certain sector by moving the production to less developed countries. Thus evaluating the relevance of these kinds of cases for the larger, abstract claim of decoupling as a policy goal should proceed with careful analysis, taking into account the limits of the cases, and phenomena like outsourcing, trade, rebound and financialisation.

What is needed?

What about the “decoupling sufficient (and, consequently, absolutely needed) for ecological sustainability”? Currently, the combined environmental impacts of the economies of the globe are unsustainable, and the economies use too much (and wrong kinds) of natural resources. Consequently, in order not to push the planetary system over decisive tipping points and material limits, the impact has to go down, and resource use has to diminish.

This means that, in terms of time, decoupling has to be continuous, until the target is reached. Periods of decoupling followed by recoupling will not be enough. The same goes for the spatial axis. Decoupling in a limited area (say, rich countries), will not be enough if it is combined, (let alone if it is directly connected) with increased impacts and material use elsewhere. Ditto for economic scope: decoupling has to embrace the economy as whole, not just one sector of it. Importantly, decoupling one environmental impact (such as CO2 emissions), as welcome as it is, will not be enough. The decoupling of one specific impact is most meaningful when it is related to processes that cause decoupling also in terms of other impacts, world-wide and economy-wide.

Clearly, the decoupling has to be absolute, as relative decoupling is, by definition, connected to increased impacts and/or resource use. And as resource use is too high, driving ecosystem and biodiversity loss, deforestation, negative land use change and so on, the needed decoupling is resource decoupling, not just decoupling relative to one specific kind of environmental impact. In sum, the ecologically sufficient decoupling is fast-enough, wide-enough absolute resource decoupling.

How fast? And what is the level of resource use that is sustainable? In the case of climate change, the collaboration of thousands of scientists has produced models that can give relatively precise quantitative values for CO2 concentrations after which specific environmental consequences become likely. In the case of resource use such models are lacking, not the least because resource use is an aggregate number that contains different kinds of materials, whose use has very different environmental effects. Consequently, the best one can do is estimate what a global aggregate number would be, if at the same time the contents of the aggregate are within limits.

One way to arrive at an estimate is to see what kind of aggregate would be consistent with specific carbon budgets. (Assuming, for instance, that the relative proportions of the contents of the aggregate stay relatively stable.) The International Resource Panel (IRP) of the UN has presented a scenario where the target is to “freeze global resource consumption at the 2000 level, and converge (industrial and developing countries)”, and assumes a global population of 8,9 billion by 2050. This scenario amounts to a global metabolic scale of 50 billion tons (50 Gt) by 2050 (the same as in the year 2000) and allows for an average global metabolic rate of 6 tons/capita. The average CO2 per capita emissions would be reduced by roughly 40% […].” and “[…] is more or less consistent with the IPCC assessments of what would be required to prevent global warming beyond 2 degrees.” (p. 32)

Pinpointing a level of sustainable resource use is difficult, and much less studied than, say, GHG gas budgets. This is, primarily, a problem for the advocates of decoupling, as it considerably decreases the usefulness of the concept. Without a clear target, the concept allows quite a bit of “hand-waving” with regard to concrete steps towards success.

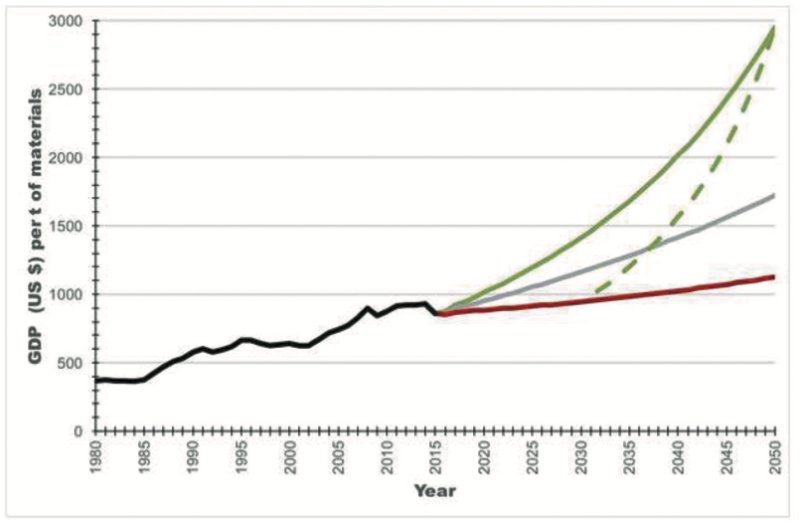

“Successful” decoupling

Proponents of decoupling typically refer to the concept so that they can keep maintaining that economic growth (in GDP terms) and less environmental damage/resource use are compatible. Very well, let us do a thought experiment: suppose that the economy grows and decoupling “succeeds”: what does such a decoupling look like? In the article “Raising the bar: on the type, size and timeline of a ‘successful’ decoupling” we defined a “successful decoupling”, for the sake of the argument, in the following way: 2% annual GDP growth and a decline in resource use by 2050 to a level that could be sustainable and compatible with a maximum 2°C global warming (with 9.7 billion as the global population by 2050, in the median range of UN World Population Prospects). The result? Compared to 2017, a “successful” decoupling has to result in 2.6 times more GDP out of every ton of material use, while the use of materials diminishes ca. 40 percent. There are no realistic scenarios for such an increase in resource productivity. Actually, global material productivity has declined since 2000. Obviously, the task of a “successful” decoupling would be even more formidable, if the goal would be a maximum warming of 1,5°C, as, for instance, in the Paris Agreement.

“Succesful decoupling” The green line depicts the scenario of material use of 7 tons per capita in 2050. The dotted green line presents a scenario where action is postponed until 2030 after which the reduction of material use is fast-tracked to reach 7 tons per capita in 2050. The (dotted) green line, in our estimation, depicts a ‘successful decoupling’, implying a modest GDP growth of 2% from 2017 to 2050, and a per capita use of materials of 7 tonnes in 2050.

We feel that this result puts the burden of proof decidedly in the camp of people promoting decoupling as a solution: please, present a detailed and concrete plan on how the economy is supposed to get 2.6 times more value of every material ton used, while cutting material use 40 percent. Given the urgency and gravity of the issue, abstract hopes pinned on innovation and technological progress are not enough.

Decoupling according to evidence

What does the literature say about decoupling? What kind of decoupling has been observed?

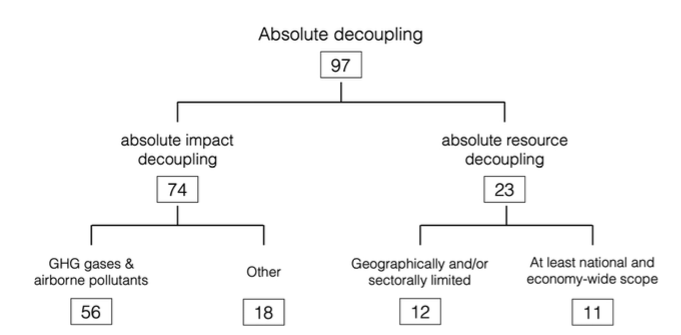

In the article “Decoupling for ecological sustainability: A categorisation and review of research literature” we did a review of 179 articles published between 1990-2019.

Like noted above, some kinds of decoupling are clearly happening. The literature finds evidence of impact decoupling (see the list of research articles), especially between GHG emissions (such as COX and SOX emissions) in wealthy countries for certain periods of time. There are extended periods of absolute impact decoupling of GHG gases. As welcome as these developments are, they are, however, i) not examples of “decoupling needed for sustainability” and ii) not necessarily connected or leading to “decoupling needed for sustainability” .

This means that there were only 11 articles that possibly are talking about the intersection in the diagram, both “decoupling observed in research” and “decoupling sufficient for sustainability”.

Unfortunately, when those 11 papers are examined, the intersection evaporates to nothing. You can check our article for details, but all of the 11 articles report limits of one or several type on the absolute resource decoupling that has been observed: limits of time, scale or depth, or several at once. This is hardly surprising as we know that globally, material productivity has been descending or flat since 2000. The general thrust from studies like Wood et al. (2018) and Krausmann (2017) is that when trade and consumption-based indicators are taken into account the recent (post- 2000) global trend is a recoupling of material use and GDP.

Summa so far

There is evidence for absolute impact decoupling, in terms of GHG gas emissions, which are going down in some rich countries while GDP is growing. This is very welcome. But it is nowhere near the kind of decoupling sufficient for ecological sustainability. Nor is it based on trends that necessarily (materially, logically) will lead to decoupling sufficient for ecological sustainability. Not to speak of being fast-enough.

At the moment, the intersection between “decoupling observed in research” and “decoupling sufficient for sustainability” is empty. This, in our mind, presents a severe challenge to any policy or strategy relying on decoupling in order to solve the pressing environmental crises.

A call for collecting research

We have published an annotated a list of research articles on decoupling (the articles discussed in “Decoupling for ecological sustainability” are included in this list), and ask all of you to contribute to keeping it up to date. The idea is, first, to keep up with what is happening in terms of the empirical evidence presented for decoupling and, second, to specifically look for evidence of the kind of decoupling needed for ecological sustainability. Here is the link. The file is hosted as an OSF project, with DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/WR5KM. (The list is also available as a Google Spreadsheet, if you prefer).

Please send e-mail to decoupling@bios.fi identifying any relevant articles that you see missing from the list. We hope that the “open source” list will help everyone stay abreast of what is happening in research, and so further discussions and research on decoupling and the related essential matters of resource use, environmental impact and sustainability.